(With the recent relaunch of The Muppet Show, the article title seemed appropriate. For those who don’t get the joke, here’s the reference.)

In the late 1970s, Science Fiction/Fantasy and Superhero movies were making a big comeback. Blockbuster hits like 1977’s Star Wars (before it was called “A New Hope”) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and 1978’s Superman. 1978 also brought us the television series Battlestar Galactica, which brought cinema-caliber special effects to television.

And right along with all of those, the performers at the Organ Grinder restaurant wowed fans with vibrant theatre pipe organ renditions of the themes from those films. (John Williams’ themes in particular were performed frequently at the Organ Grinder, all the way up to 1993’s Jurassic Park.)

Trivia: There is a tangential Battlestar Galactica connection to the Organ Grinder. Many of the “blinkenlights” on the set of Battlestar Galactica were genuine Tektronix oscilloscopes and other equipment, including the display terminal that Commander Adama would use to narrate his logs. The real-time transcription displayed on those terminals seemed impossibly advanced at the time, but now machine transcription is a feature of most smartphones. Tektronix is the Oregon-based tech company co-founded by Howard Vollum. Howard plays a key role at multiple points in the Organ Grinder’s history.

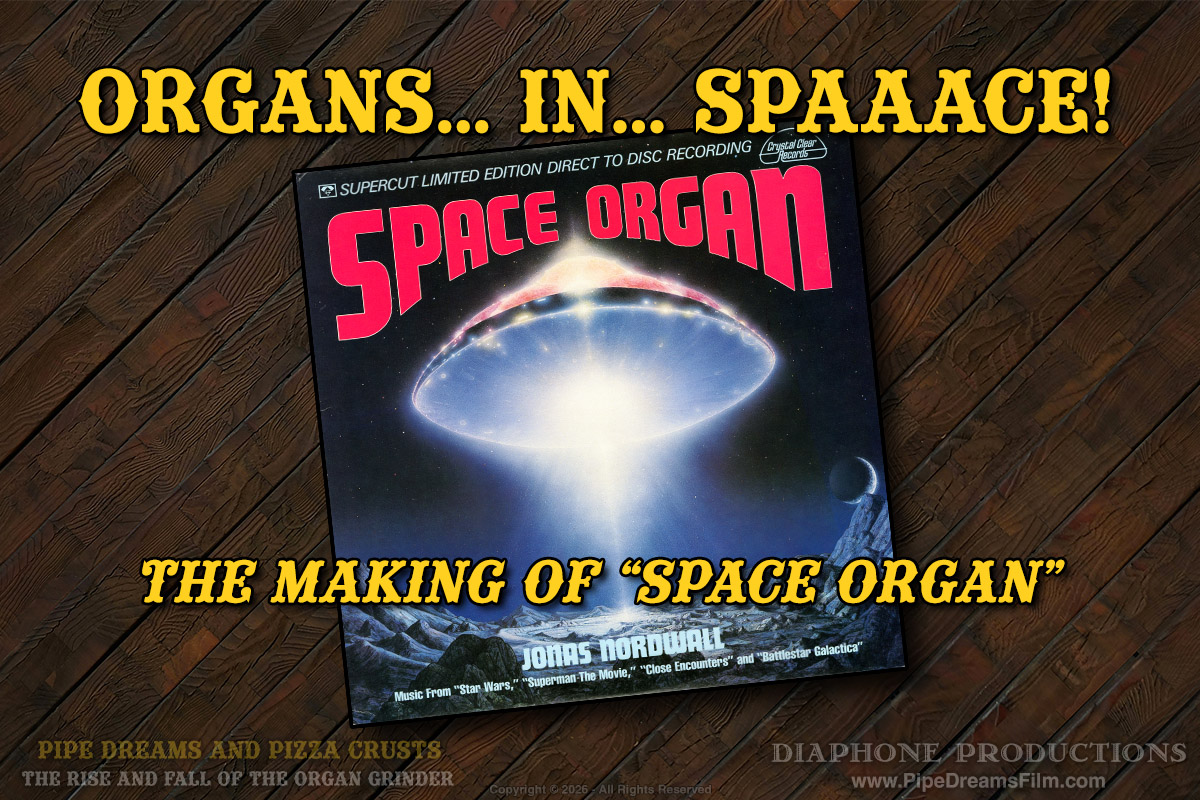

In 1979, striking while the marketing-hype iron was hot, producer Ed Wodenjak of Crystal Clear Records, recruited organist Jonas Nordwall to make a record album of four popular themes: Star Wars, Superman, Close Encounters, and Battlestar Galactica.

Crystal Clear Records (now-defunct, the current company with that name is not related) specialized in making Direct to Disc recordings, which were popular with audiophiles and collectors at that time. Some argued it was the best quality and dynamic range you could get from a vinyl record album – at a time before compact discs were available.

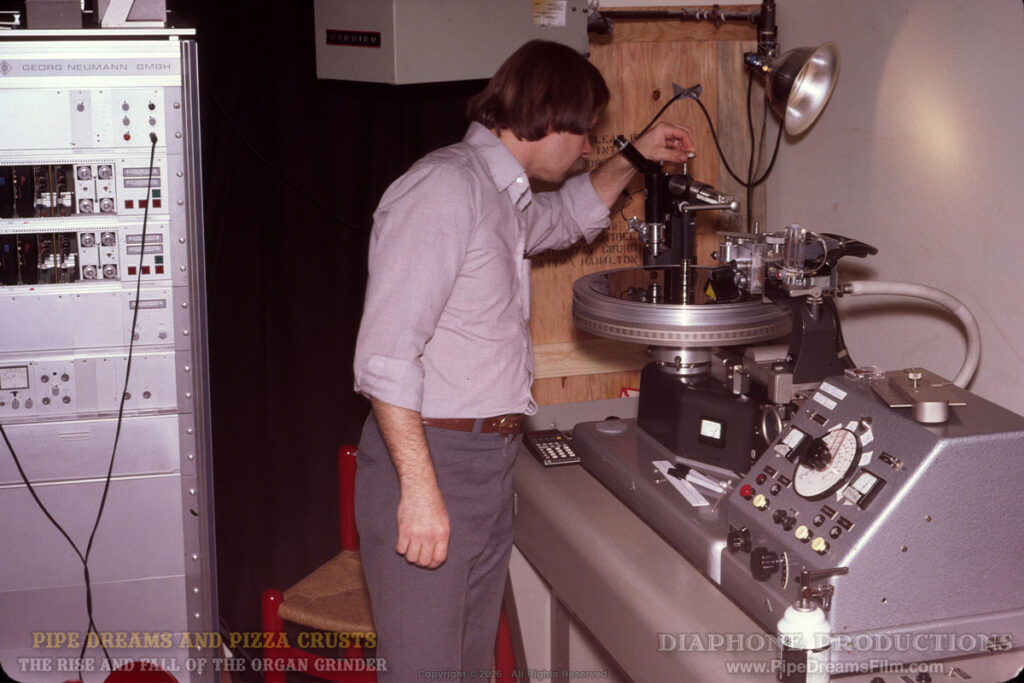

Ed and his crew, live-mixing engineer Pat Maloney and disc-mastering engineer, Larry Van Valkenburgh, brought an array of specialized recording equipment to the restaurant in April, 1979. Organ Grinder co-founder Dennis Hedberg, no stranger to the art of making quality pipe organ recordings, recently provided his recollection of the process:

Making a direct-to-disc record is tricky business. In the photo with organist Jonas Nordwall, you can see one of the two microphone stands and a very full music rack. Nothing can be left to chance.

The Producer/Director, a Mr. Wodenjak, pushed Jonas to make his performance ever-more aggressive and more violent with each rehearsal.

The production team came with at least a dozen blank lacquer discs. It was a good thing, because many takes could not be completed due to either Jonas stopping for whatever reason, or lathe errors.

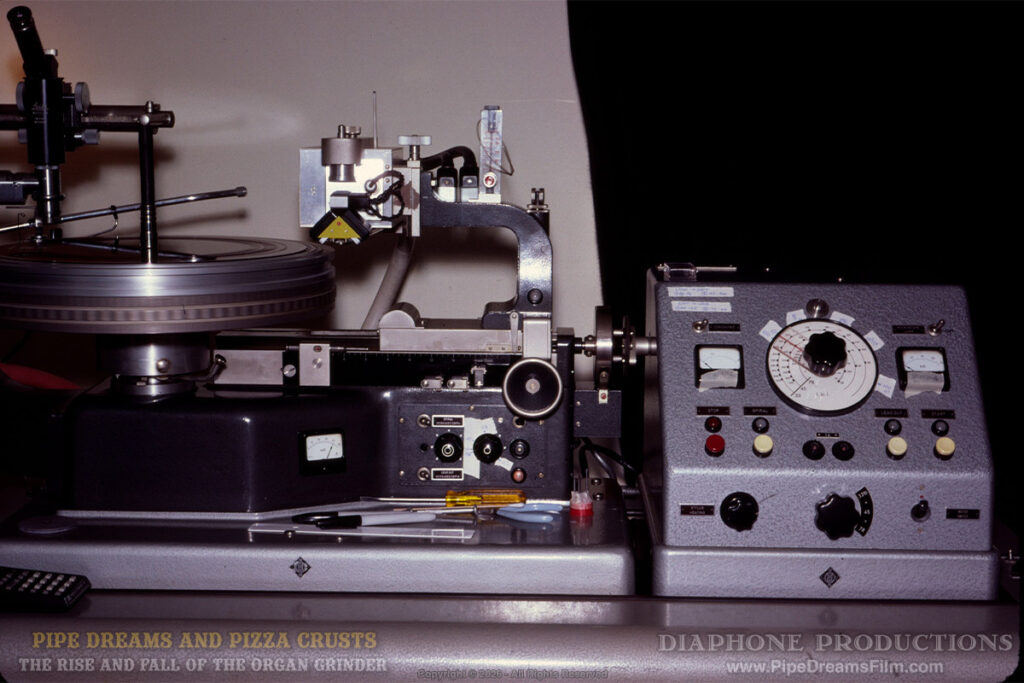

The Neumann disc cutting lathe is a wonder to behold. Its operator is rightfully called the Mastering Engineer. You can see him in one of the attached photos. The lathe is equipped with its own microscope so the engineer can closely examine the groove pitch and amplitude.

It stands to reason, the louder the music, the greater will be the cutting stylus’s horizontal and vertical movement. This means groove-to groove-spacing must be greater so its pitch is set wider. But, the wider the pitch, the shorter the record’s playing time will be.

In stereo recording there is also a vertical component to the cutter’s stylus. In the extreme case, when left and right channels’ polarity are opposite to one another, the stylus moves straight up and down like hill and dale. This means if the signal level is too loud, the stylus could rise above the lacquer’s surface – or strike the lacquer’s substrate. Either will ruin the take and probably the cutting stylus, too.

Notice the large knob in center of the cutter’s control panel. This control determines groove pitch. The Mastering Engineer will narrow the pitch for several lacquer revolutions for the lead-in, break between tracks, and a very wide pitch for lead-out.

Considering Space Organ’s program material, with its high volume and extended low frequency bass, the required pitch would be wider than most, and that explains why the Star Wars Medley playing time is only 13:21, and the Superman Medley and Battlestar Galactica is only 11:59 – when most records are around 18 minutes playing time per side.

With the count of blank lacquer shrinking, the notion of letting the Mastering Engineer manually adjust track pitch was abandoned – instead settling for a track pitch wide enough to permit cleanly capturing the loudest passages, at the expense of shorter program time.

(There was a tape backup made of each ‘take’. I asked the producer if I could have a copy of the backup tape for my own library; after all, their recording could not have been made without my assistance, but my request was rejected.)

Although Space Organ has been out of print for a very long time, copies still turn up occasionally on eBay and record trading sites such as Discogs.

Thank-you to Dennis for writing up his memories of the recording session, and for providing the accompanying photographs.

You can help support the project by purchasing from the Crowdfunding Shop.