(Post updated 2025-07-13 with technical info.)

In this newly-acquired footage from the 1970s, organist Jonas Nordwall performs a full set at the Organ Grinder restaurant in Portland, Oregon.

This compilation is from vintage video tapes which were recently provided to the documentary project.

Sometime around 1977, representatives from Sony visited the Organ Grinder to test an improved pro video camera for its low-light and dynamic range capabilities. (1977 is a guess based on feedback from people involved with the Organ Grinder based on what features of the instrument and the restaurant are visible in the footage – and, of course, the fashions.)

The format was 3/4″ U-Matic, a workhorse industrial video standard.

These tapes had sat unwatched for over 40 years until now, and are the best quality video shot at the Organ Grinder from that era found so far.

The audio was recorded in true stereo, which is rare for the time.

After a painstaking restoration, we happy to be able post the contents of the tapes so that fans of the Organ Grinder can re-live these magic memories. Read on after the song list below for more technical info…

Song List:

- Theme from S.W.A.T – Barry De Vorzon

- Unidentified – If you recognize this song, please Contact Us or let us know the title in the YouTube comments!

- Train Sequence & Chattanooga Choo Choo – Harry Warren and Mack Gordon

- Tiny Bubbles Version 1 – Combined with Invention #14 in B-flat Major (BWV 785) – Leon Pober and Don Ho, J.S. Bach

- Music! Music! Music! (Put Another Nickel In) – Stephen Weiss and Bernie Baum

- The Washington Post (March) Version 1 – John Philip Sousa

- The Stripper – David Rose

- Consider Yourself – Lionel Bart

- Beth – Peter Criss, Stan Penridge, and Bob Ezrin (KISS)

- Tiny Bubbles Version 2 – Combined with Sleepers Awake (BWV 140) – Leon Pober and Don Ho, J.S. Bach

- Somewhere, My Love (Lara’s Theme) – Maurice Jarre

- Sabre Dance – Aram Khachaturian

- The Washington Post (March) Version 2 – John Philip Sousa

- Fernando – Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus (ABBA)

Technical Info:

1. The Tape Format

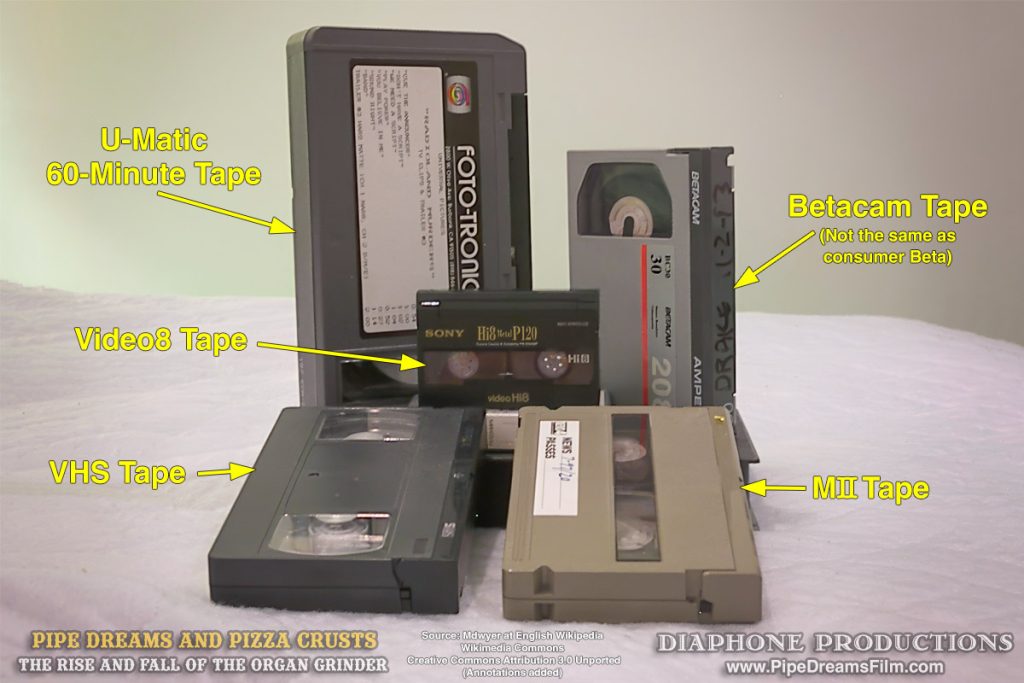

Two tapes were found. One was a larger, 60-minute tape, and the other was a smaller, 20-minute tape. The 3/4″ U-Matic format had tapes in two sizes – a “compact” tape (larger overall than a standard VHS tape) for portable recorder units, which had a capacity of 20 minutes of recorded video. The larger tapes, meant for studio editing and on-air playback, could hold 60-minutes. Here’s a visual comparison of various tape formats:

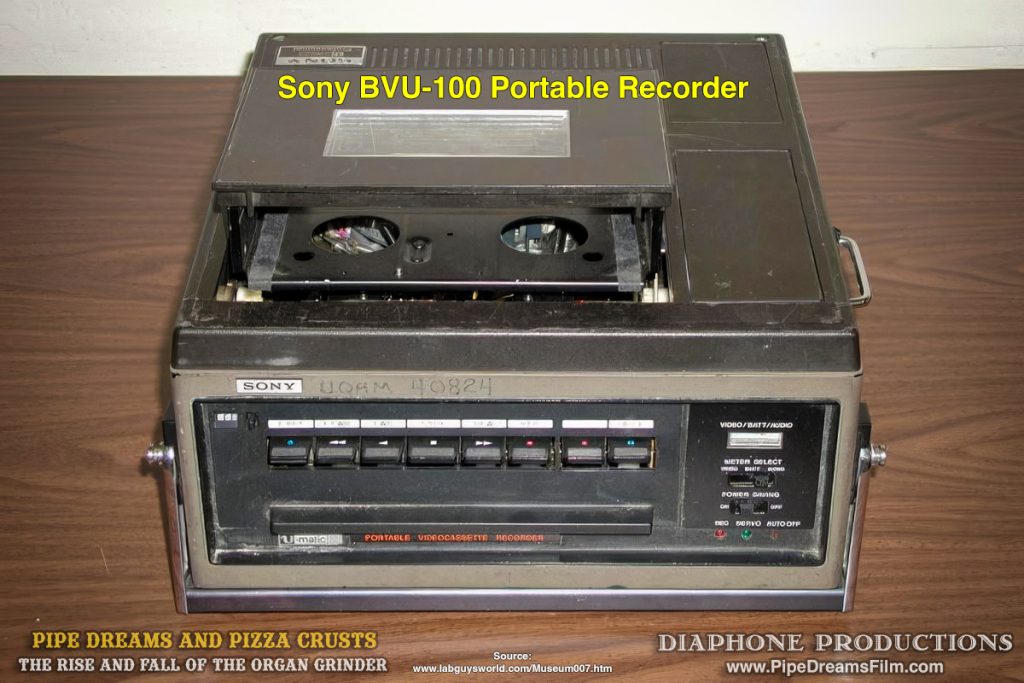

The tapes were not labeled with what exact camera was used, but one did have “BVU-1000” written on it. The BVU-100 was Sony’s “portable” field recorder unit, which was like an oversized briefcase that could be worn with a shoulder strap (and a battery belt!) – the camera was separate, either mounted on a tripod or held over the shoulder.

While the camera is not know, it was using a Vidicon tube as a sensor, as evidenced by the “comet-tail” streaks on large bright objects when the camera pans across them. This also supports the late 1970s assumption of when the video was recorded. (By the late 80s pro cameras were mostly using CCDs.)

2. Digitizing the Tapes

The tapes were digitized on our rig which supports a variety of formats:

For 3/4″, a Sony VO-9850 VTR was used. The 9850 was one of the very last pro editing decks that Sony made in this format, from the 1990s.

There is a problem with a lot of vintage tape formats – they get “sticky” over time and will jam and gum up tape decks, and get damaged in the process. This was due to a bad tape formulation manufactured in the 1980s, and 3/4″ was hit especially hard:

Fortunately, and a bit ironically, these two Organ Grinder tapes were sufficiently old that they were unaffected and played back perfectly.

The VTR was fed through a Digital Processing Systems “timebase corrector” (TBC). This is a piece of TV studio equipment that corrects the small timing issues inherent in playback of analog video tapes, so that the signal is suitable for editing, often synchronized with other players, and also suitable for broadcast. This particular TBC is a later model that outputs a digital signal called “SDI”, again used in broadcast studios. SDI is still a widely-used standard, now supporting high-definition video.

This SDI output made it possible for modern devices to record the standard-def video at the highest possible quality. A Blackmagic Design Video Assist 12G 7″ recording monitor was used for this purpose. This is the same monitor is used for recording the majority of the new footage for the documentary, at 5.7K resolution. But, because it supports SDI, it also supports all of the previous standards, including good-old standard-def NTSC.

The tapes were digitized to Apple ProRes format at 10-bit color depth – meaning that there are 10-bits each of red, green, and blue, compared to consumer formats today which usually have 8-bits. Those additional 2 bits work out to 4X more color information being recorded in each channel. This means we are able to get the best possible quality out of these tapes when converting to digital, way better than using the consumer capture devices currently on the market. It may seem pointless, given the low resolution of analog standard-def video, but squeezing out just a little bit better quality results in impressive results as the footage gets processed with modern tools.

3. Sorting out the Content

After reviewing the digitized footage, at first there was a bit of a mystery, as some of the same footage was present on both tapes. In this description, the tapes are referred to as “Big Tape” (the 60-minute cassette) and “Small Tape” (the 20-minute cassette).

After some scrutiny, and making a list of all that was found, the following conclusions were reached:

The first half of the Big Tape contains footage that is not on the Small Tape, but is otherwise unedited. Given that the videographer wouldn’t have taken a full-size recorder around with them, it is assumed that this is 2nd-generation footage copied from some other tape that has not yet surfaced.

The second half of the Big Tape contains what is clearly a 2nd generation copy of the raw footage from the Small Tape (there is an obvious difference in quality), but with some edits made adding footage from the pipe chambers and of the sign. These edits also contain footage that must come from some other tape.

This all means that the Small Tape consists entirely of raw footage recorded directly from the camera, and that there is probably more raw footage out there on one or two additional tapes (of which we have the edited 2nd-generation version).

4. Cleaning Up the Footage

The camera used had an “interesting” tendency to skew bright colors, especially light bulbs, toward magenta, while simultaneously skewing the shadows toward green. Further complicating things, was that the color of Jonas’s jacket was within the range of this magenta skew. This meant that a global set-and-forget color correction setting would not work.

The photographer also adjusted exposure as the lighting conditions changed (for example, when the console spotlight was turned on during the bits when the mechanical monkey was brought out), and earlier in the evening, the photographer hadn’t quite settled on the ideal exposure. This affected several variables, including just which items were affected by the bright/dark color skew.

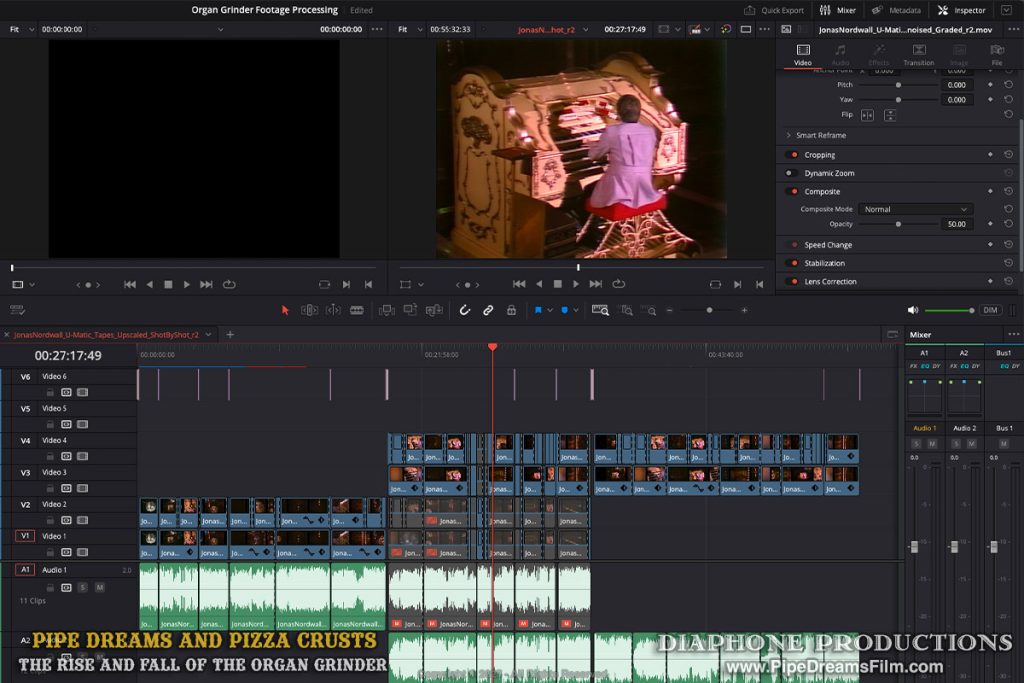

Color-correction was performed in DaVinci Resolve Studio v19, which is also the main editing software for the documentary.

The first task was to adjust the exposure of the image to compensate for changes made by the photographer, creating an even exposure throughout, creating keyframe animations of these values, as the change might occur gradually over a second or two.

The image was split into two separate channels, bright and dark. The dark channel, representing what was in the shadows, was shifted away from green (toward magenta is the traditional approach), and also the dark areas were brightened as best as possible, with temporal noise reduction applied. (Temporal noise reduction compares previous and future frames to the current frame, to try and determine what is real detail, and what is noise in the recording that can be averaged out.) The end result is still rather dark, but it is much better than before.

The bright channel was further refined to just look at the magenta tones created around bright object (sometimes called “color flares”). This especially affected the light bulbs running up the columns, which should appear amber-tinted, but instead looked purple. The effect is still visible, because compensating for it completely looked artificial in the end, but it is also much better than before.

The final problem was that the bright-channel correction would ruin the appearance of Jonas’s jacket. So, the effect is dialed back whenever the jacket is brightly lit or fills most of the frame, using another keyframe animation.

After several rounds of tweaking and reviewing adjustments, the files were exported to a new intermediate file, with these color decisions “locked down”. The use of an intermediate file speeds up future steps, as some processes such as noise reduction are computationally intensive.

5. Upscaling and Enhancing

The files were then run through a program called Topaz Video AI. Topaz uses various artificial-intelligence models to analyze and enhance footage. (This is somewhat different than the AI people see on the web, that “makes up” entirely new images based on millions of images absorbed into their model – which is controversial for many reasons including that other people’s copyrighted works are often used to train the models.)

While still arguably “generative” in nature, the Topaz models attempt to fill in missing detail based on what they recognize should go in those spots. Topaz does exceptionally well, for example, with the gold flourishes that decorate the console. Topaz completely falls apart, however, when it recognizes that there is text but can’t make out the actual letters – it replaces that text with very sharp, but completely made-up gibberish. This was most evident on the stop tabs. It would not only put garbage text all over them, but it would decide that the ends of the tabs needed to be square instead of rounded.

The specific model used was called “Rhea” – This is a very computationally intense model, which ties up the whole computer. Even a high-end editing workstation with a fast GPU, in this case, took about 18 hours per hour of footage to process – the whole time with all the CPU cores and the GPU usage pegged, with the fans which you normally can’t hear running full blast – like having a vacuum cleaner next to your desk!

The final rhea output, while sharp, also makes everything look plastic, glossy, and fake with the default settings. This was dialed back as much as could be done without losing the detail enhancement that was desired, but it can still look distractingly fake without further processing after Topaz.

To overcome the issues of “plastic” appearance, and false detail choices such as text and squaring off rounded objects, a second upscale process was done to the intermediate footage (not the Topaz output) using DaVinci Resolve’s built-in “Super Scale” feature, which while not nearly as sharp, looks much more natural than Topaz. This was output to a separate file.

Finally, the two files were superimposed and blended, most of the time 50% Topaz/50% Resolve, which appeared the most natural. When the camera zoomed in to the console, showing the stop tabs, or whenever an area of detail appeared incorrect because of Topaz’s decisions, the blending was gradually shifted to 75% or more Resolve.

6. Final Steps – Redoing the 1970’s Edit

As mentioned earlier, it was determined that the Big Tape contained edited material, some of which came from camera-original footage on the Small Tape.

Again using DaVinci Resolve, the exact edit decisions made by the original videographer were redone using the higher-quality footage from the Small Tape wherever possible. The Small Tape also contained better, original audio, which was used to replace audio in the edited version as appropriate.

Finally, the songs were reordered (a subjective decision) to a more logical and pleasing progression than the original edit, and graphics/titles were added to create the YouTube version you can see at the top of this post.

Just one song was omitted, “Happy Birthday”, due to crowd noise and the fact that good number of folks don’t particularly care for that song! It might be released in the future as a stand-alone version, much like Paul Quarino’s Happy Birthday rendition that has already been posted.

7. Conclusions and Acknowledgements

Today’s video tools provide powerful features for rescuing and improving the appearance of vintage video footage, although even the most powerful “AI” tools still require thoughtful human oversight to make sure that the end result makes sense and isn’t distracting to the viewer.

Could something more be done for this footage? Of course! Talented Hollywood colorists and editors wouldn’t stop at just separating bright/dark regions in this case – individual objects (such as Jonas, or the mirror ball, or the stop tabs) would be tracked separately and split into separate “nodes” that can all be processed differently, with the appropriate type and amount of processing applied. The level of work involved, compared to the benefit, would be difficult to justify for the documentary, given project priorities. But, the improvement seen by doing what has been done is rather amazing and quite satisfactory. (If any experts out there would like to take a crack at their own restoration, we are happy to provide the footage with a basic copyright agreement in place.)

A special thank-you to Colleen Robbins, who has contributed to the documentary in many ways, but in particular purchased the license for the entire Topaz suite (which includes other programs for still photo enhancement) for the project during a Black Friday special last year. It’s not a cheap piece of software – even with a discount! It has been immeasurably useful (despite its bugs and idiosyncrasies) in many aspects of production.

Lastly – a search for the original videographer. The tapes were not labeled with the videographer’s name. If anyone knows who created these recordings for Sony, please contact us, as we’d love to give them credit. The Big Tape also contained home video footage (possibly of the videographer and a family member or friend, or someone else that the videographer was recording), and that footage can be provided to the family/friend if the videographer can be identified.

You can help support the project by purchasing from the Crowdfunding Shop.